A Relative Stranger Who Was Dear to My Heart: Becoming Better-Acquainted with "Our Own," An LGBT Newspaper Based in Norfolk, VA

When first I moved to Hampton Roads in 1998, I'd never been in a gay bar, save for one impromptu visit with friends to a place in Charlotte, NC several years prior.

After the elapse of a few to several months as a resident of the region, I managed to summon the courage necessary for me to visit such an establishment solo, and although the first couple of experiences were better than I'd feared, frustration fairly quickly set in. As it were, I was encountering difficulty in finding my people -- be that men who had sufficient interest in being friends outside the darkness of the bar and with whom we shared enough in common to sustain such a relationship, or dating material.

Being a late-bloomer who'd spent most of his life in places with no gay scene whatsoever, I wanted to find my tribe and I wanted to date, and I felt keenly the passage of time and, occasionally, the loneliness of my reality.

This far removed from that point in time so many years ago, I can't say with any degree of certainty whether I saw my first copy of "Our Own" in a bar, or whether, perchance, I might've snagged a copy at the Naro Expanded Cinema, a coffee shop, or a newspaper box. I do, however, seem to have vague recollections of collecting a paper from a place other than a bar, and folding it in on itself to try to conceal its contents from anyone who might've been paying attention.

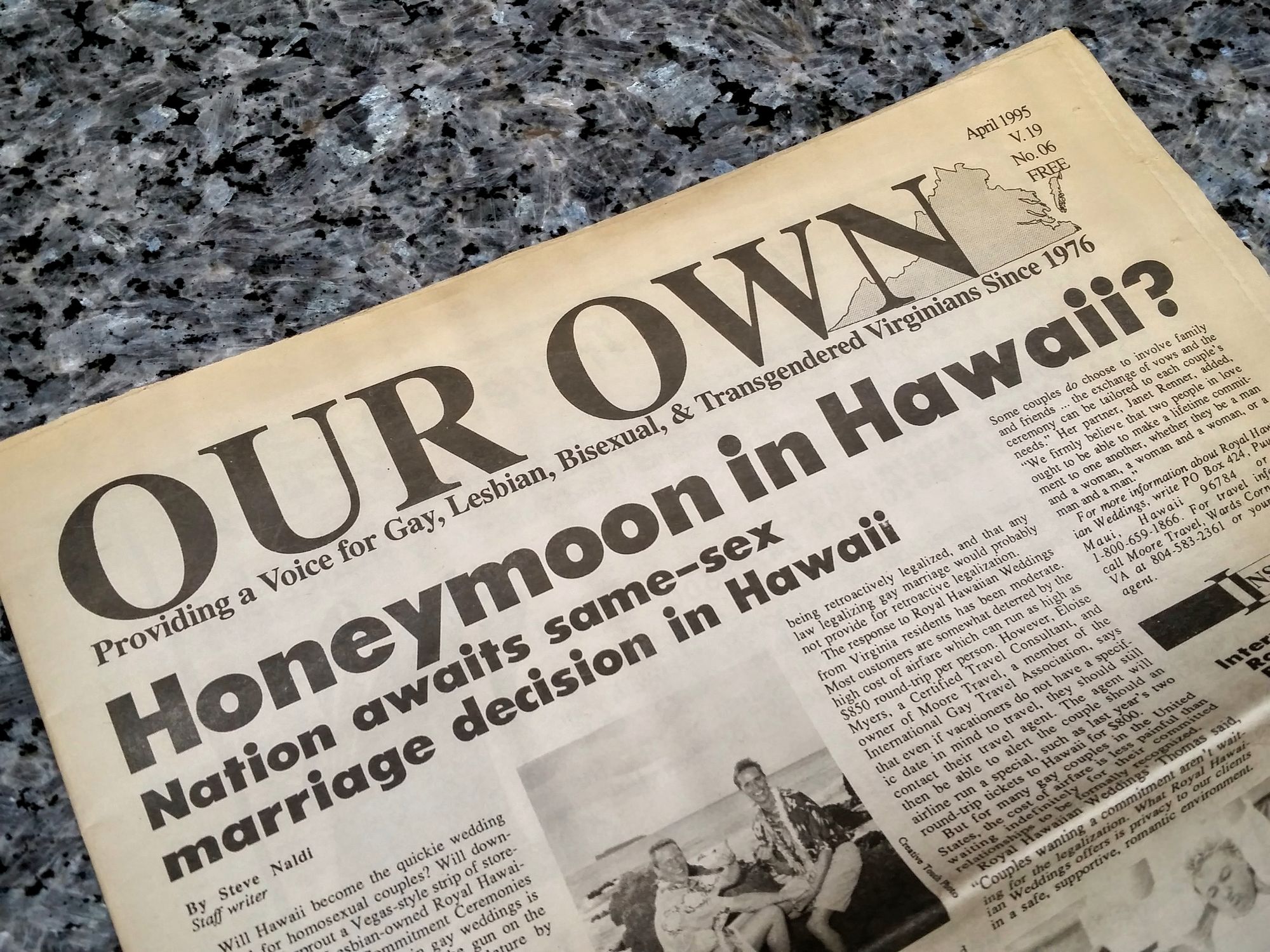

Nonetheless, I do recall that my eagerness for the arrival of a new copy of the LGBT newspaper was considerable. Though I had little in the way of a frame of comparative reference, I deemed the quality of the publication to be strong and laudable for an area of its size. Additionally, the staff didn't confine themselves solely to the reportage of local LGBT news; they published stories from elsewhere, as well, which, in an era that preceded the web as we know it today, was welcome, as it helped to imbue a sense of perspective on gay life beyond the immediate environs. (Truth be told, though, I always hungered for more local content.)

They also ran book reviews and other such material, which, in concert with the overall look and feel of the paper, provided it with some cultural teeth and a bit of a learned feel, considering that it was a paper focused on LGBT-related issues that was produced by people who generally had other day-jobs that paid their bills.

Of course, ads from bars were numerous, and, paired with the editorial content and one's own prior experiences, these helped guide decisions about where to go, and when, in my search for a more fulfilling gay experience.

In any event, though, since I was experiencing continuing frustrations in finding my tribe, I thought volunteering with the paper would be a fantastic way to meet folks in a non-bar setting, particularly since I had relevant skills of writing and photography that I could contribute. I suspect that that idea was also motivated by a fascination with editor Kirk Read, inasmuch as an out, gay man with a flair for written language was not exactly common in these parts (and arguably still isn't).

Alas, however, before I could present myself for consideration as a volunteer, the paper ceased operations, this after apparently having been the longest-running, continually-published LGBT newspaper in the nation, churning out stories from 1976 until the presses fell silent in 1998, just a few months after I'd landed in Hampton Roads.

And with its demise, so vanished a sense of community that I felt that it helped to foster by serving as a spine that connected the disparate tendrils of gay life in Hampton Roads. Indeed, in so doing, I think it magnified the appearance of the LGBT life that did exist here at that time, perhaps making it feel more expansive than it might actually have been. For me, its pages seemed capable of conveying the suggestion that something more was possible, that perhaps I'd find that tribe or that guy or my niche. In some respects, it was my tribe, and a lifeline of sorts. Reading it was a little bit like holding hands, with its words, event calendar, and ads teasing the possible and furnishing the hope that attaches to possibility.

Since I respected so much the mission of "Our Own" and how well they were executing it, yet simultaneously got to see only a few new editions as a resident of Hampton Roads before publication ceased, I suppose a mystique, of sorts, surrounded the paper for me. I'd been given a sip of its words, which only made me want a gulp.

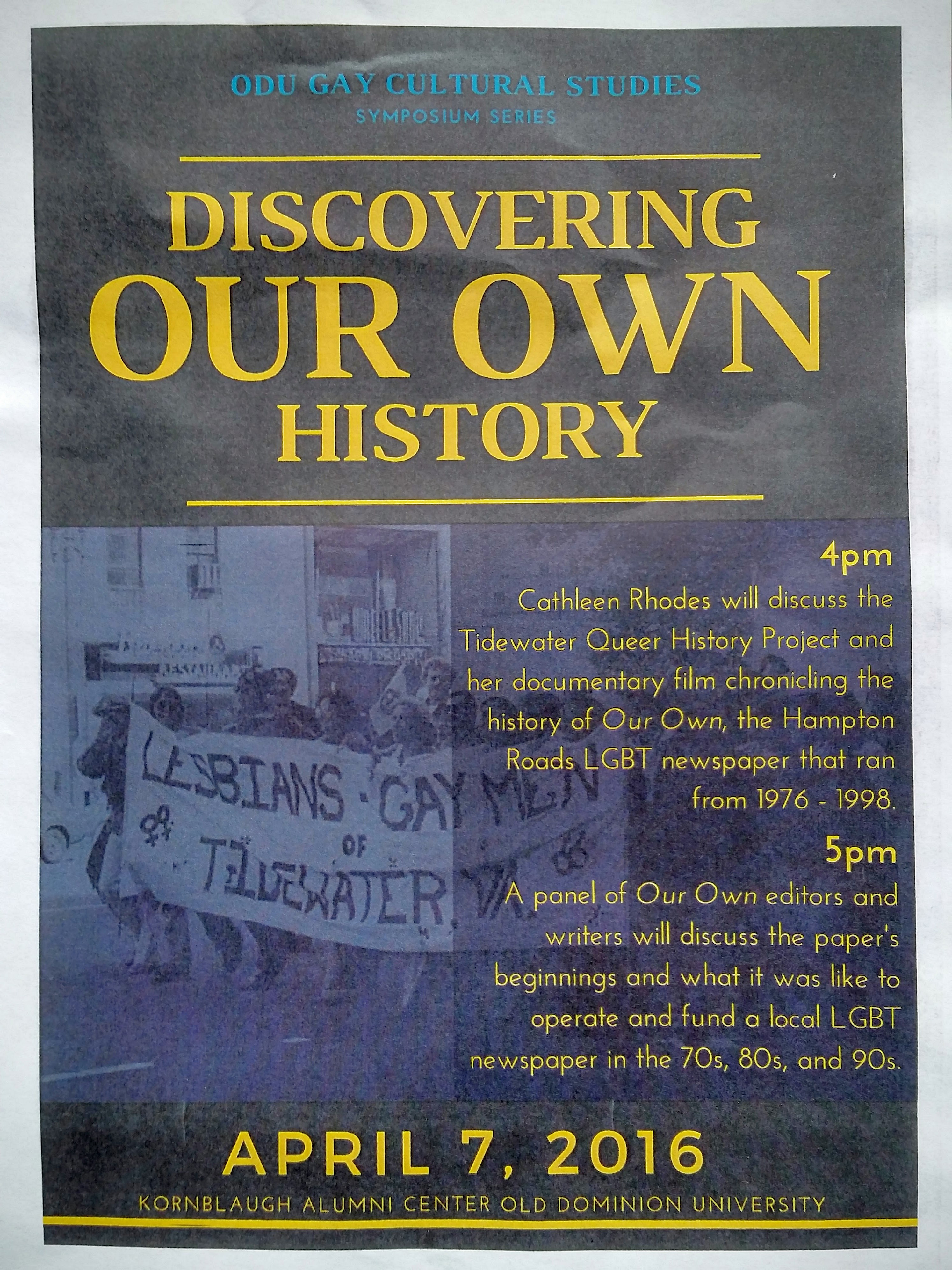

In view of that, I was beyond excited when, at the book launch and signing event for "Images of Modern America: LGBT Hampton Roads," Cathleen Rhodes, of Old Dominion University, recognized me from having been introduced at a festival late last year and mentioned an upcoming symposium she'd be hosting at ODU that pertained to "Our Own." The flyer she handed me (pictured below) stoked much enthusiasm on my part, and though I expressed doubt I'd be able to attend, given the weekday timing, I very much wanted to do so.

Promotional flyer for the ODU symposium.

Promotional flyer for the ODU symposium.

Thankfully, though, work was such that I was able to make it.

Over the course of an hour-long presentation this past Thursday afternoon, Ms. Rhodes walked the audience through the history of "Our Own," from its commencement as a one-page, letter-sized document birthed in 1976 at the Unitarian Church of Norfolk, through to its conclusion in 1998 as a tabloid-format paper with scores of pages.

The slideshow and summations were punctuated with the screening of a few segments from Ms. Rhodes' upcoming film chronicling the history of "Our Own," the production quality of which -- in the form of the camera-work, sound, editing, and graphics -- was impressive, and amplified my desire to see the finished product.

The next hour of the program consisted, as the flyer said, of a panel of "Our Own" editors and writers.

What struck me most about the group was the apparent affection these folks still have for one another, as well as the continuing evidence of the passion that drove them to do what they did, and what I'd describe as a reverence for the publication and what it achieved.

Watching and listening, I was reminded of the people who were the focus of "How to Survive a Plague," which told the story of those who pitched in and helped out during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, trying to assist the afflicted and agitate for government help to secure treatments for the dying. A couple of the folks in that film actively expressed how grateful they were to have been able to do meaningful work and bring about some positive change, and how, in their current lives, they missed doing work that so engaged their hearts and drew together so many to work to better the community. One might say that they missed the camaraderie of caring souls.

Really, I got the sense that at least a couple of the panelists might've felt quite similarly about their work on "Our Own."

But to me, those who work to advance civil rights and to create community -- and these are things "Our Own" achieved, in my estimation -- are heroes. Folks who do such work are the types of folks I view as rock stars. And indeed, these were people who devoted massive amounts of their free time -- often late at night and into the early hours of the morning -- to produce this newspaper.

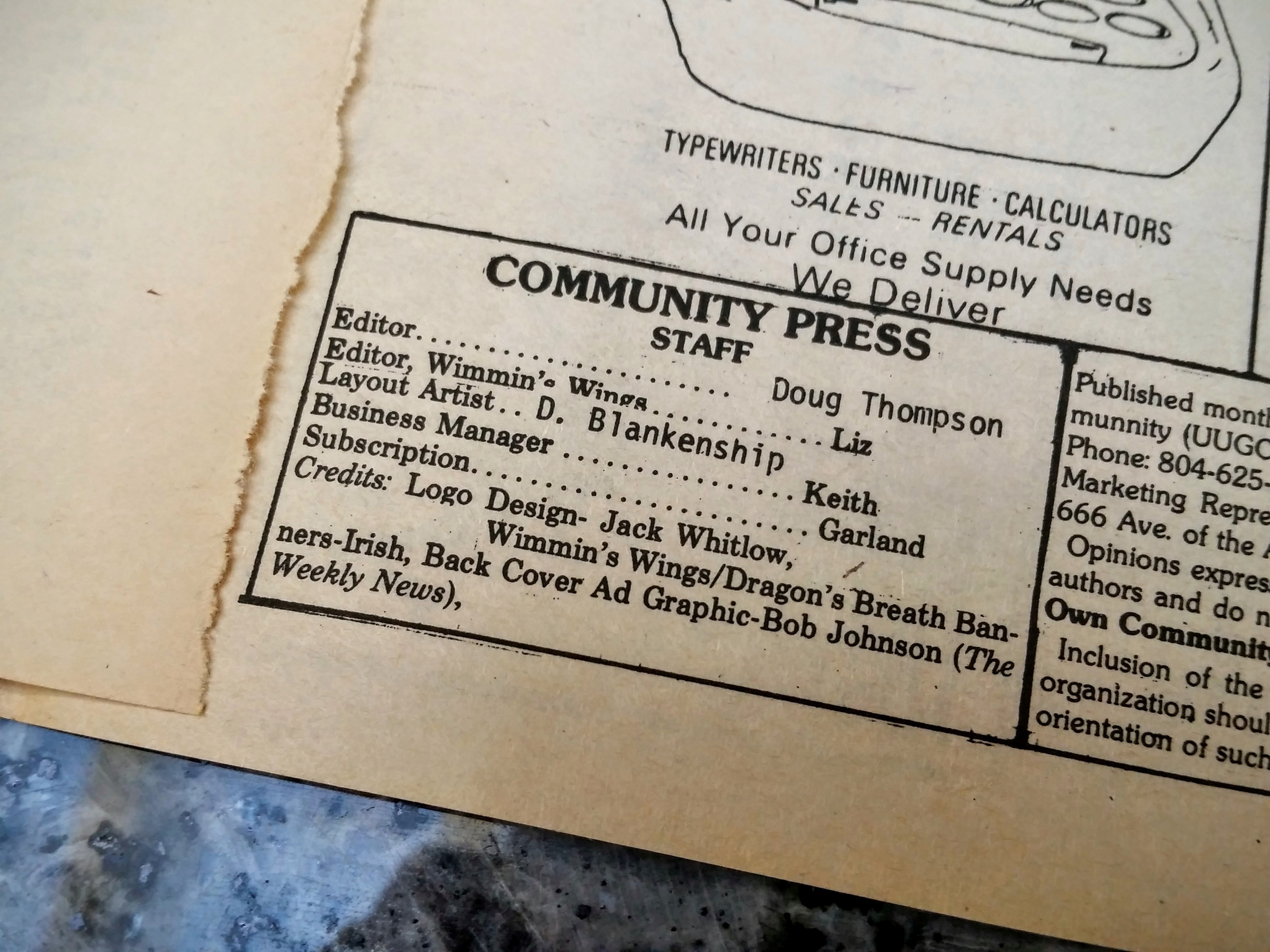

Listening to them reminisce and comment, it was evident why I perceived the paper as being a quality publication, as they certainly attempted to uphold standards of design, typography, and journalistic integrity and practices, even though such areas were not necessarily those in which the participants had been trained for their primary careers, and resources were limited. However, I gather that the individual with the most amount of pertinent knowledge in a given area would educate the others as best he or she could.

They spoke of difficult decisions, including having been asked by the partner of a man who'd been murdered not to run the story. (Though not voiced explicitly, my inference, given the context, was that the partner of the man killed was either concerned about being outed himself, or about his partner being outed posthumously.) However, they ran the story anyway, as they felt that, in light of the circumstances, someone else might be exposed to a dangerous risk of violence if they were unaware of what had transpired.

In another instance, in a report about an assault that happened outside of a bar (if I recall correctly), the victim (or a victim) phoned the paper and asked that the story not be run, saying he'd be disowned by his family if they learned of his sexual orientation. This request the staff honored, though the last-minute request required a scramble to find something else to occupy the space that had been devoted to the story.

Alicia Herr spoke of delivering papers in more rural areas and being hugged by people who were so grateful that "Our Own" existed, since, through it, they realized that they were not alone and they felt less isolated.

And with regard to volunteers helping the paper, one of the men said that it was not uncommon that when a Navy ship would come into port, eight or nine people would find their way to the newspaper's offices and ask if there was anything they could do to help (and this would've been long before "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" was repealed, of course, and quite possibly before it existed, depending on the era).

Meanwhile, there were apparently times when the newspaper's staff felt that their office phone was tapped, and they reportedly witnessed individuals noting or photographing the license plates of vehicles parked near the building when the paper was being worked on. (Presumably, the latter would've been associated with law enforcement or military investigative services, which would be consistent with other accounts I've read and heard over the years pertaining to the monitoring of parking lots of LGBT clubs and bars.)

List of "Our Own" staff from the 1980s, with full names omitted, except for the editor.

List of "Our Own" staff from the 1980s, with full names omitted, except for the editor.

Though it all sounds quite incredulous, just a few short decades ago, the realities and freedoms of LGBT people were most assuredly wildly more harrowing and confining than has become so in the last ten years, though make no mistake that in 2016, many politicians aligned with the religious right are doing their best to legislate a rollback of the progress that's been made.

And yet, efforts to produce the LGBT newspaper also ran into turmoil and tension from within the community itself, one example of which was that many of the women apparently found the ads for the phone-sex chat lines for men to be unseemly or too explicit. Yet, without them, the paper couldn't go on. (Eventually, such ads were moved to a separate, pull-out tab to enable those who didn't wish to see them to easily dispose of them.)

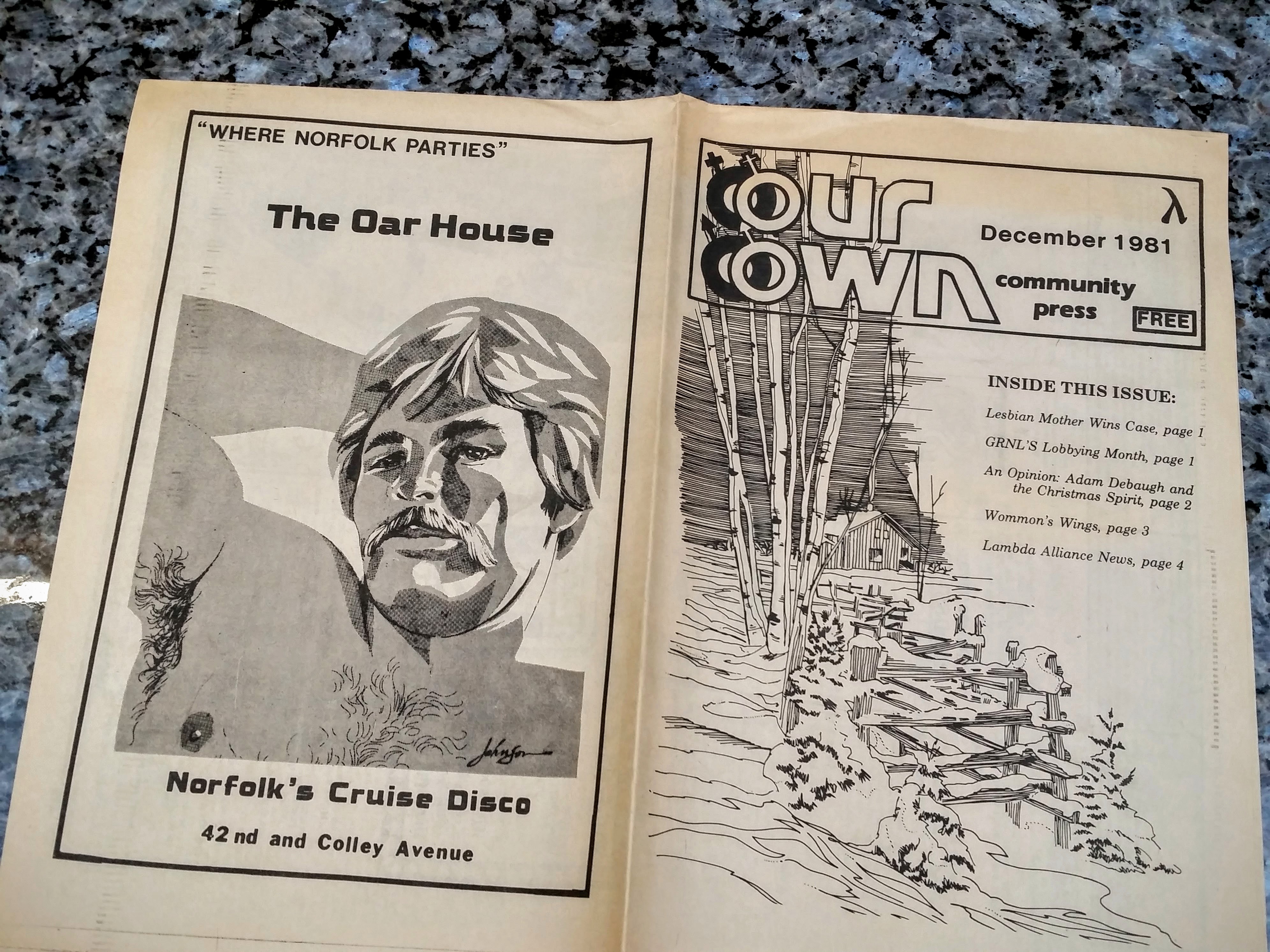

Bar ad and "Our Own" cover from December 1981.

Bar ad and "Our Own" cover from December 1981.

Similarly, ads for LGBT bars were a key source of revenue, yet bar owners were not always pleased with the editorial coverage that included reference to their facilities with regard to crime and other such activity. Further, the paper was substantially dependent upon the bars for distribution, and one of the men said that he was aware of instances in which bars whose proprietors or management were unhappy with coverage involving the establishments had simply tossed into the garbage their entire allocation of a new edition of the paper.

And further to the point concerning revenue from bar ads, I found it noteworthy that the panelists mentioned that a man who'd worked for the paper for about three weeks before his employment was terminated then went on to launch "Out and About," which was, in essence, little more than an advertorial for the local LGBT bars. The bedrock of their content revolved primarily around showcasing the pretty-boys of the nightlife set, highlighting the aspects of bar life that cast it in the best light, and conveying thinly-veiled gossip concerning who was dating, or doing what, or had been seen with whom.

Indeed, I inferred from the panel discussion that "Out and About" likely captured a sufficient share of local gay bar advertising that that loss of revenue was one factor amongst several -- including increased expenses for office space and payments to staffers, whom they were trying to offer a decent wage -- that helped to accelerate the demise of "Our Own."

In any event, after the discussion concluded, I was truly grateful to be able to tell the panelists how much I appreciated their labors and their service to the community, and to let them know how much I respected the work they'd done.

None of them had I ever before met, to my recollection, and they all received the praise humbly and with appreciation. When I related my past plan and intention of volunteering, most of them remarked that they'd have been glad to have had my help. Ms. Herr commented that they'd have taken me right in, and she rose to hug me as she was about to leave.

A bit later, after I'd paused to talk to Ms. Rhodes and then began walking to my car, I caught up to the panelists as they were getting into a vehicle. They waved, and they all -- but particularly Ms. Herr, who'd not yet gotten into the car -- looked at me with such kind, welcoming eyes brimming with sentimentality, empathy, and understanding.

I'm confident I'd have enjoyed my service with the paper, had our timelines better-aligned.

According to my brief chat with Ms. Rhodes after the symposium, her documentary film about "Our Own" is at least a year away, with more filming still to be done. I look forward with enthusiasm to its debut.

To keep track of its progress and associated activities, visit the Facebook page for the Tidewater Queer History Project.